Mask lessons were learned (and resisted) 102 years ago

The mask zeitgeist has shifted, now that President Donald Trump wore one in public. He said on July 1 that he thought it made him look like the Lone Ranger, even though that Western icon wore a mask across his eyes rather than over his mouth and nose — that was for bad guys. Critics have zeroed in on Trump’s Johnny-mask-lately conversion, wondering how many lives might have been saved had he embraced his inner Lone Ranger earlier.

Nevertheless, the topic of masks and wearing them is still hotly debated, often in retail chains as iPhone cameras roll. These videos have prompted questions: Was there resistance to masks during the 1918 pandemic? Did they work? How was mask wearing enforced in the old days?

Quick answers: Yes, there was resistance and defiance, masks worked to limit or stall the spread of disease, and mask-wearing was sometimes enforced with fines, arrests, jail time and, in at least one case, gunfire.

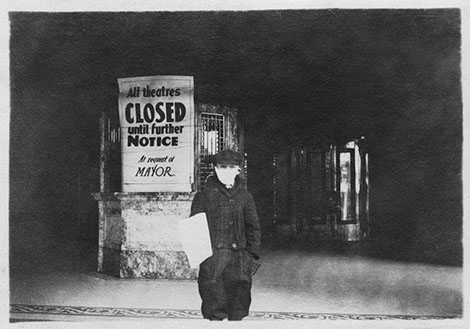

After scouring press coverage on the West Coast during the 1918 flu era, I can say resistance to adopting masks wasn’t universal, but it also wasn’t uncommon. In Seattle, during the influenza’s lockdown period in October and November of 1918, people without masks were banned from public transit and ticketed or fined by members of the police’s masked “Flu Squad.†Headlines had a somewhat negative spin: “Thousands Are Hit with Flu Mask Order,†shouted one in the Seattle Star.

The masks recommended during the 1918 pandemic were made of heavy-duty six-ply cotton gauze. They were thick and no particular joy to wear. People who refused to wear them or couldn’t be bothered were called “mask slackers†or “mask scoffers.†During World War I, the term slacker described people who neglected their patriotic duty, almost as bad as being a draft dodger.

In Walla Walla, the chief of police, John Haven, refused to enforce a state mask mandate. He pointed out that he was going to meet heavy resistance and had no authority to carry out a state directive, only city ordinances. Still, he also openly defied the instructions of the city’s health officer, J.E. Vanderpool, to follow the state health officer’s guidance.

Even as people dropped dead in Walla Walla and rural southeast Washington, business owners pushed to have their establishments — saloons and billiard halls — reopened in defiance of advice from most doctors and health officials. The Walla Walla police chief’s determination not to enforce a state edict is mirrored today by a number of sheriffs in rural Washington who have said they will not enforce Governor Jay Inslee’s mask requirements. The sheriff of modern-day Lewis County told his people, “Don’t be a sheep.â€

Yakima was less reluctant to crack down on scoffers and slackers if they were doing business with the public. The city’s sanitation inspector arrested 15 people for “working or transacting business in a public place without wearing gauze masks prescribed by the city health commissioner,†according to a 1918 article in the Spokane Spokesman-Review. The problem was the merchants, not their customers. The business community held that the city had no authority to mandate masks.

Then, as now, health officials were divided on whether masks truly prevented the spread of Spanish influenza. Many understood that the chances of transmission were worse in enclosed public spaces, like churches and movie theaters, but opinion was divided on the efficacy of masks outdoors. Some believed the fresh air fought the flu, and encouraged people to open their windows and let in the bountiful breeze.

Mainstream medical belief held that going maskless could spread contagion. The multi-layered gauze masks appeared to work in reducing new cases, and they proved effective for medical staff treating flu patients.

Other physicians claimed the masks themselves became an unsanitary health hazard if not cleaned and sterilized. Dr. J. C. Bainbridge, a prominent physician from Santa Barbara, Calif., claimed, “The common use of the mask tends to propagate rather than check influenza.†Others simply argued that masks had no effect. However, historians generally believe that social distancing and masks saved tens of thousands of lives since there was little else that proved truly effective, such as vaccines and serums.

Still, divided opinions and often localized health authority meant communities responded differently to the pandemic. Seattle and Spokane, for example, were generally mask-compliant. Spokane, in fact, had trouble keeping up with the public demand for masks, and many of the coverings were hurriedly made and ill-fitting. The Spokesman-Review featured photographs of professional women in masks under the headline, “Women in Business Life Don ‘Flu’ Masks.†There was less enthusiasm in Portland, which didn’t pass a mask ordinance, with one city council member objecting that he would “not be muzzled with a mask like a hydrophobia dog.â€

The San Francisco Bay Area saw reluctant acceptance of masks at first, then massive pushback. A mandatory ordinance, announced in bold headlines on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle in October 1918, read: “Wear Your Mask! Commands Drastic New Ordinance.†It blared over the mugshots of city leaders masked up like surgeons. Many equated mask compliance with patriotism and the war effort, an appeal that worked for many prior to the end of WW I with the signing of the armistice on Nov. 11, 1918, mid-pandemic on the West Coast.

In Seattle, a similar narrative took hold. Once people were free of their masks, they refused to go back to them, even as flu cases started to rise again. A Seattle Post-Intelligencer editorial in December 1918 warned that reinstating health edicts would spark fear not of the flu, but of an excess of “regulatory zeal.†There was no indication, the editorial opined, that “another shutdown of business and revival of the mask would be tolerated.†Compliant Seattle was done with compliance.

Many observers of the time believed masks helped flatten the pandemic curve. When it came to stifling dissent, however, they proved an ineffective muzzle.

Reprinted with permission of Crosscut, a non-profit news site (crosscut.com). Knute Berger, who wrote this article,

is Crosscut’s editor-at-large.