How the fair got here

By Paula Becker

On Oct. 4-6, 1900, a group of Puyallup Valley farmers, business people, and other residents join together to produce an agricultural and livestock fair designed to highlight local products. The event is called the Valley Fair and is so successful that it becomes an annual event. In time it will become the Western Washington Fair Association’s Puyallup Fair (since renamed the Washington State Fair) and draw the fifth-highest attendance of any fair in the country.

The main promoter of the Valley Fair was Lewis Alden Chamberlain, a farmer from Buckley who successfully mounted a similar agricultural event in Enumclaw in 1899.

Alden set about convincing farmers in the Puyallup-Sumner Valley that their location would make it easy to draw crowds from as far away as Seattle and Tacoma. Chamberlain approached the Puyallup Board of Trade with his idea. The board gave the project their support, and in June of 1900 some of the valley’s most progressive farmers organized the Valley Fair Association. Chamberlain was elected president of the newly formed association. William Hall Paulhamus became vice president, James P. Nevins secretary, and George D. Spurr treasurer.

Board members circulated through the valley offering $1 shares of 1,000 possible shares of capital stock they had issued to fund the fair to merchants, farmers, and anyone else they could corral. Although only $82 was raised through stock sales, and some of that was the value of trade labor rather than cash, board members pushed ahead with preparations, erecting a 10-foot fence around a vacant lot west of Puyallup’s Pioneer Park.

As they busily set up a borrowed tent within the fence on the evening before the planned Oct. 4 opening, gusts of wind collapsed it. It took until after midnight to re-pitch the tent and repair the damage.

The Valley Fair board, however, had evidently not managed to stir up sufficient local enthusiasm. When the gate opened, no exhibitors had yet materialized. Vice president Paulhaumus recalled events in a newspaper report in 1920: “Chamberlain stood at the gate most of Thursday morning without any exhibits being turned in. About noon, Romulous Nix was seen coming down the dusty road leading a shorthorn bull, unknown breeding. [Nix’s name was actually Rhonymous or Ronimous. Apparently he used both spellings but usually abbreviated it and used the name R. Nix.] Mr. Chamberlain gave his old friend a warm greeting and found a fencepost to which the Nix bull could be tied. The bull had some qualifications besides being the head of the herd. He had also been taught to permit boys to ride on his back, and instead of having a merry-go-round or a Ferris wheel, the children were entertained by taking a ride on the back of the Nix bull.”

Paulhaumus arrived soon thereafter with a heard of Jersey cows, some calves, a wagonload of chickens, ducks, and geese, and some Berkshire hogs. With the Nix bull, they constituted the fair’s initial livestock exhibit. By the time the event concluded, several horses and foals and an owl had joined the exhibition.

Examples of the Puyallup-Sumner Valley’s bounteous produce were on display inside a tent, as were various kinds of needlework, baked items, and jams and jellies. Contestants vied for prizes in categories such as best raspberry wine, most butter made in 24 hours, and best example of Hubbard squash. A pair of slippers was promised to the child under age 16 who produced the best essay on Puyallup Valley history. A number of valley merchants also displayed their wares.

A $1 admission fee covered an entire family for the entire run of the fair, and also gave that family one vote in the election of fair officers for the next season. Newspaper writers were admitted free of charge.

Although attendance on the fair’s first day was disappointing, by Friday, Oct. 5, word of mouth had spread and the trickle of visitors began to expand. Local residents attended almost without exception, and, true to Chamberlain’s prediction, Tacoma residents began to arrive by train.

Friday’s fair visitors watched as infant Walter Durgan of Sumner was awarded the prize for Prettiest Baby. A public wedding planned for early afternoon had to be canceled when the engaged couple who were to have been married and collect an oak rocking chair and $10 worth of groceries as wedding presents developed cold feet. A cattle parade around the fairgrounds led by Oscar Showers of Enumclaw and a brief horse race helped disappointed fairgoers regain their good humor.

The first Valley Fair netted a profit of $583 and drew some 3,000 visitors. Except during World War II, the event was held annually thereafter. By the end of the 20th century, more than 1 million people attended the Puyallup Fair (as it was titled then) each year.

Source: Historylink.org, a non-profit organization, and Washington Department of Archeology and Historic Preservation.

FAIR, FOOD, FESTIVITIES: IT’S THE FAIR

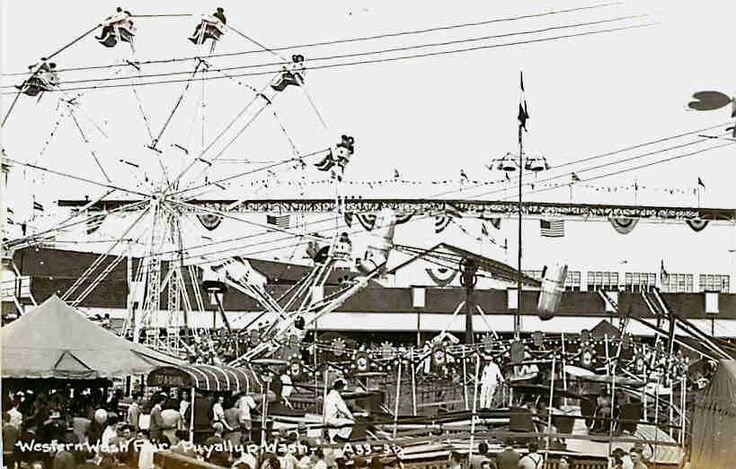

This year’s Washington State Fair, in keeping with one of its annual traditions, will open in Puyallup on the Friday of Labor Day weekend. The 20-day run Sept. 1-24 (it will be closed on all three Tuesdays) will feature the usual attractions, including animals (farm and domestic), agriculture displays, commercial vendor and product exhibits, carnival rides and game booths, arts, and food (such as the fair burgers the two past fairgoers have their hands on in this photo). Big-name musical performers will star in the concert series at the grandstand, where a rodeo is also billed.

The fair is the largest one in Washington and one of the biggest in the world. Some things to know if you’re planning to attend:

- Wear comfortable shoes and expect crowds. The fairgrounds cover 165 acres, and attendance averages 1 million people a year.

- Admission costs $14 for adults, $12 for children 6 to 18 years old, and $12 for seniors. Kids 5 and under get in free. Everyone can enter free on opening day between 10:30 a.m. and 12:30 p.m. by donating a non-perishable food item for the Puyallup Food Bank.

- Parking in official fair lots costs $15 on weekdays and $20 on weekends. “Premium” parking (purchased on-site) is $35, and VIP parking (purchased online) is $50. Private owners and fund-raising groups typically offer pay-to-park options. And there is some on-street parking.

- Need other information? Call 253-841–5045 or go online at thefair.com.